To casual listeners, the word reggae has become a catch-all term applied across the board to any musical release coming out of Jamaica since the early 60s. But to anyone who takes a closer listen, it’s hard to imagine that the synthetic electro styles played in the dancehalls of Jamaica the last couple of decades are considered to be the same kind of music as the bouncing 60s beat of bands like the Skatalites. And in fact, most avid fans of Jamaican music absolutely do not consider those styles to be the same genre, and ironically neither are actually “reggae” (we’ll get to that in a little bit). Like rock’n’roll, “reggae” is a constantly evolving music that is comprised of many different sub genres that have came and went and sometimes came back again over the fifty plus years of modern Jamaican recording. So I’d like to try and shed some light on the unique characteristics of the bigger, important sub genres, and also give some insights into telling the difference between them all.

The Roots

If Jamaican music is a tree, then the root of that tree is American rhythm’n’blues and jazz. To understand the development of the Island sound, you have to start in the 50s, a few years before any Jamaican artist set foot in a recording studio to record “popular” music. At that time, almost all of the trained musicians were working in the hotels playing jazz for tourists and the more colloquial folk music like mento (think Jamaican Calypso, though that’s not exactly the right way to describe it) was to be found around the island, from yards to the beaches.

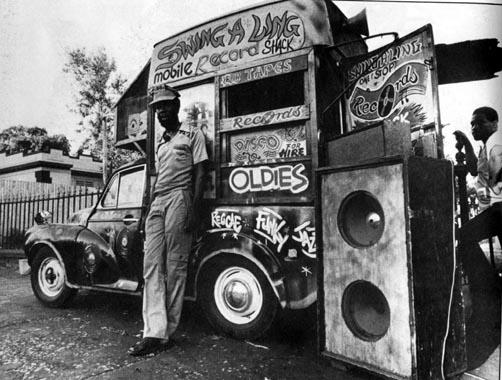

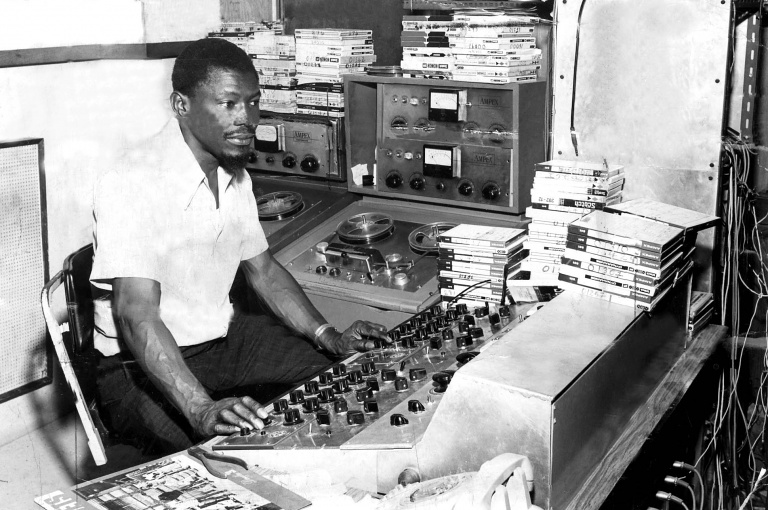

Recording technology was rapidly expanding worldwide and the 45 had emerged as the soon-to-be-dominant medium, but the equipment was still a little cost prohibitive in the Jamaica of the fifties. But a few industrious men pulled together the necessary pieces of equipment, much of it homemade, and began hosting dances featuring the latest American records played earth shakingly loud along with some food, alcohol and games of domino. This soon became THE form of entertainment for the local, less affluent Jamaicans who lived in the capitol city of Kingston. The sound men, as they were known, built their sound systems as loud and dramatic as possible and made their reputations on the records in their box. Those records were almost solely American rhythm and blues, obtained through a chain of hands made possible by emigrating workers who travelled back and forth between the island and the southern parts of the United States.

The name of the game was to have sounds that no other sound man had, and the identity of the records was a closely guarded secret. By the end of the fifties there were several big sounds on the scene, the biggest and most competitive being Coxsone Dodd’s, Duke Reid’s, and Prince Buster’s. These three names should be familiar to most reggae fans, and for good reason. All would go on to make significant contributions to the development of reggae in the sixties. But their starts were as sound men, not DJs quite exactly as we think of them today, but nevertheless records were their reputation and “live” music not at all a concern of theirs in the late fifties. But at a certain point, and it’s disputed as to exactly why or how they each arrived at this conclusion, they decided to cut records for themselves.

Some argue that the style shift in the US from r’n’b to rock’n’roll was not received well in Jamaica, but the most compelling argument is that it became obvious to the sound men that the best way to have a record that absolutely no one else had was to make it yourself. The first to go into the studio was Coxsone Dodd (his first efforts were just rehashed rhythm’n’blues), quickly followed by Reid and Prince Buster. The musicians who played on the recordings consisted of the jazz players mentioned earlier, who made their living at the beach front hotels but resided in Kingston and were game to make a few extra dollars for a few hours of work. Were it not for this original urge to make exclusive records for the dances, it could have been much longer before any modern yet quintessentially Jamaican music coalesced out of the various influences coexisting on the island.

SKA

As a style, ska retains much of the characteristics of American rhythm’n’blues. There’s the rolling boogie woogie bass lines, traditional verse-chorus structure and prominent horn arrangements. The tectonic shift came with the rhythm of ska, which shifted the accent beat from a kick drum on the 1 and the 3 beat to the 2 and the 4 instead. This wasn’t without precedent, especially in the southern part of the US. Listen to Fats Domino and you can hear that bouncing beat. But the accent in ska was upfront and undeniable, and came to be known as the “one drop”, arguably the single most important element in the development of reggae. It was immediately noticeable and created a rhythmic backbone on which a new genre could rest. The drummer provides the beat but the accent was hammered home by the guitar and horn with staccato notes. As applied in ska, it was a driving uptempo dance floor filler, but later developments would see the “one drop” applied across all tempos, creating new styles in the process.

Despite arriving late at the dance as far as recording was concerned, it was Prince Buster who really laid the trail for ska. Dodd and Reid were so consumed by their rivalry as sound men that they missed what was right in front of their faces, that is, the opportunity to create something unique and new. Buster was the underdog, and as such he was looking for a way to differentiate what he was doing from everyone else. He named his sound “the Voice of the People” and infused his operation with fierce local pride. In his vision the crowd and their preferences was a magical Jamaican stew, and he always celebrated the beauty of the island people, the REAL island people. So when he went into the studio it was with a real intent to create something “Jamaican”.

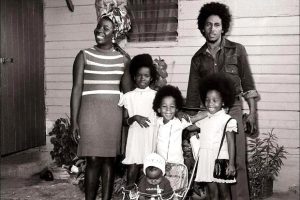

For his first recordings he enlisted the help of professional drummer Arkland “Drumbago” Parks, who connected him with guitarist Jah Jerry and trombonist Rico Rodriguez. But perhaps the most important thing Buster did was to invite the Count Ossie Group to the session. The Count Ossie Group were Rastafarian nyabhingi drummers from Warieka hill, and the decision to incorporate this element into the music would have reverberations for years to come. For one thing, it established the all-important connection between modern Jamaican music and the Rastafarian faith, a connection that would bring forth many fruitful musical moments, but more importantly at the time it cemented Prince Buster’s reputation as a man of the people, a voice for the new sound of the island, a sound made for and by the everyday Jamaican.

Once Buster unleashed his vision of ska, everyone else was playing catch-up. Legend has it that Duke Reid was dismissive of the new sound, convinced it was a fad but was forced to come around when his dance attendance hit all time lows. Soon all the sound men were pumping out ska records, and soon after that they made the leap from making “exclusives” (records specifically to be played at the dances) to starting full-fledged record labels. The records were sold anywhere and everywhere, from ice cream parlors and hair salons to liquor stores and stereo equipment suppliers. Anyone who has seen “Rockers” knows the hustle, and records became a way for poor people to put a little money in their pocket, as well as a way to spend that money. The Jamaican record industry was up and running, and from ‘62 until ‘66 ska reigned supreme.

Click on the link below to listen a playlist of early Jamaican Ska music put together by Adam Hester of Denver Vintage Reggae Society.